Trans Methodologies

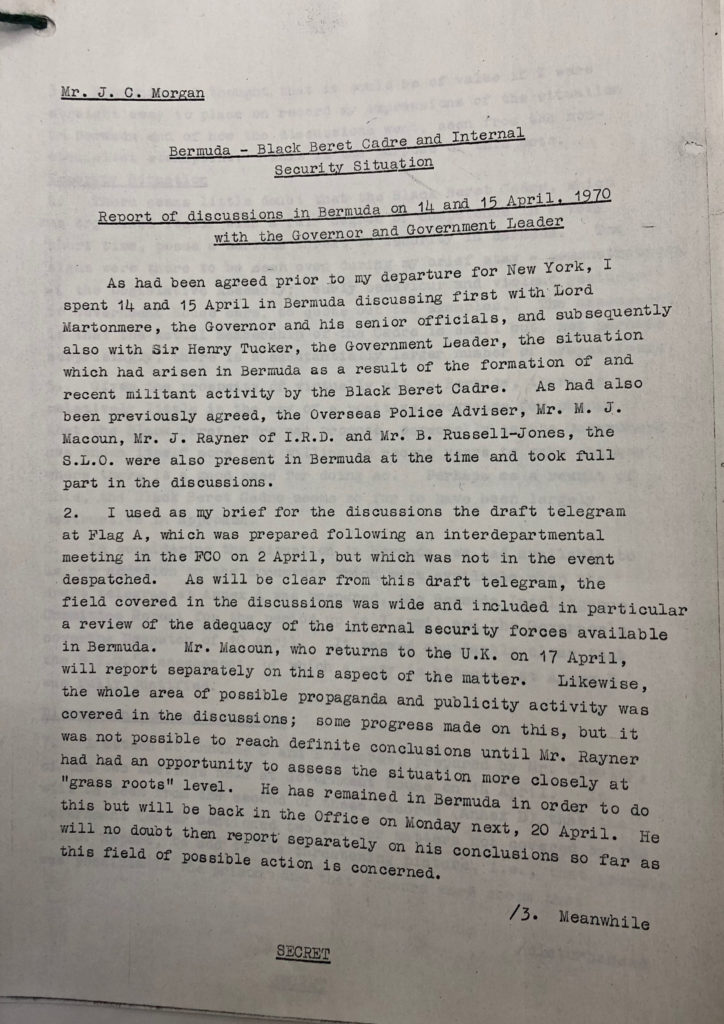

I am a Black trans visual artist using archival records as source material for painting and drawing. This allows me to share moments from history with an audience who may otherwise never visit an archive. In my doctoral research I am excavating records from the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) to examine Britain’s response to Black Power organising in the English-speaking Caribbean in 1967–76. In this, I am using my own visual language to disentangle this critical moment from the wider narrative of Independence in the English-speaking Caribbean, bringing in other voices that are not present in the records.

The significance of Britain’s efforts to suppress Black Power in the Caribbean cannot be underestimated. These actions have had severe and lasting implications, not only in the Caribbean but also in Britain. An example of this is the Immigration laws introduced in the UK and British Caribbean territories during this time period to limit the freedom of movement for Black Power activists. These laws have remained in place as the foundations for what has now become a divisive anti-immigration model in the UK.

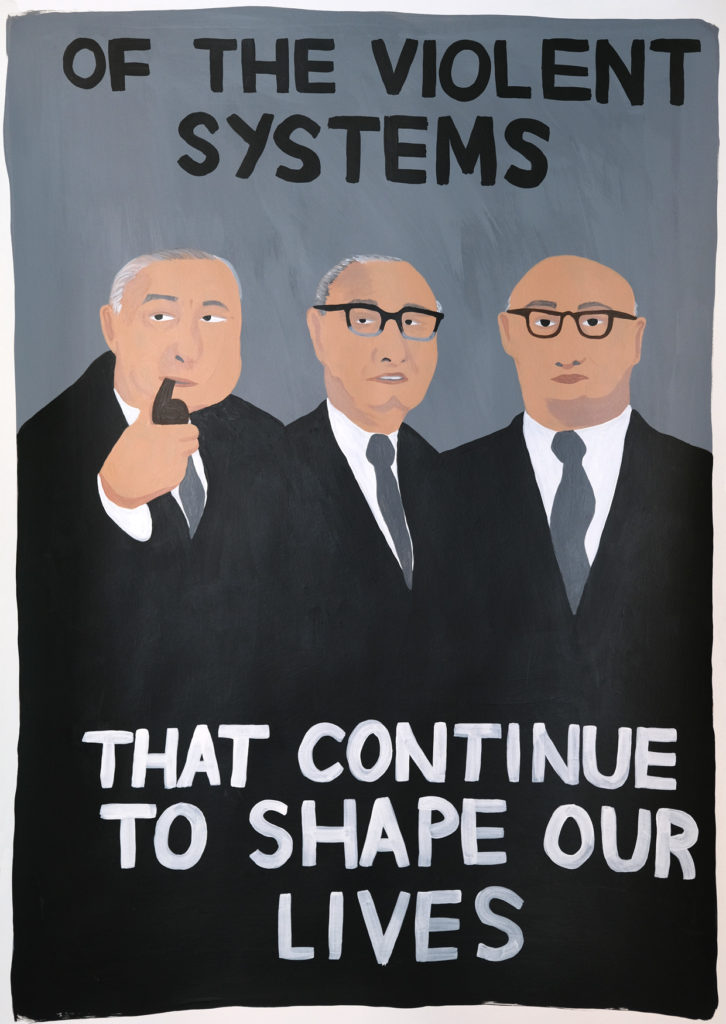

I wonder what templates were created, in what ways the Caribbean has been a testing ground for British and U.S. government operations to suppress movements of Black resistance. There are reverberations between how Britain has responded to contemporary resistance like Black Lives Matter in the UK and Caribbean Black Power movements. It is vital that we can identify and expose the continued techniques harnessed by the British government that render Black embodiment an impossibility.

The use of ‘embodiment’ here is framed by a context of Black, queer and trans scholarship. Academic Kara Keeling refers to the ‘modes of embodiment’ existing outside of systems of ‘property, ownership, dispossession, white supremacy, and misogyny’.¹ This essay is rooted in what writers Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith describe as self-determination ‘as a theoretical and embodied practice’.² Scholar C. Riley Snorton creates space to see transness as ‘a movement with no clear origin and no point of arrival’ and Blackness as a signifier of ‘an enveloping environment and condition of possibility’.³ These practices of embodiment return us to the body, as an act of self-determination.

I was driven to engage with this work because it felt so clear that this was one moment amongst many that exposes Britain as an imperialist, colonial, power. Even though a dominant narrative around Caribbean independence is perpetuated, it is very apparent that independence was conditional. As political scientist Louis Lindsay writes, ‘No sooner was the right to independence conceded in form, than it was withdrawn in substance’.⁴ I cannot help but think about how the political landscapes and trajectories of Caribbean Black resistance has been shaped by Britain’s involvement at this moment.

The FCO records offer concrete examples of strategies, such as surveillance and propaganda, that were employed by the British government to eradicate any potential for radical change that Black Power might have in the Caribbean. These documents, which are held by and at The National Archives, began undergoing declassification in 2019 and are still being released for public access.⁵ In my work, I intend to show that the state is an unreliable narrator with regards to its own history. The dominant narrative of Britain’s withdrawal from the Caribbean is at odds with what these records reveal.

In this work I am developing a trans methodology to unravel this complex history into visual works. This methodology envisages a future world with embodiment at its centre. This would make those systems of oppressive power referred to by Keeling impossible. My methodology is structured around questions such as: ‘What if Black Power movements in the English-speaking Caribbean had been successful in nurturing radical change for the communities and practices they fostered?’; ‘What would it look like in the English-speaking Caribbean to go beyond the hold of British colonial ideologies?’. To imagine Black embodiment requires moving beyond these colonial ideologies, including those about gender and sexuality. To do so, my trans methodology builds upon the vision of Caribbean Black Power activists fighting for self-determination. Author and activist Leslie Feinberg reminds us that trans liberation benefits everyone, cis and transgender alike. Indeed it means ‘each individual’s right to control their own body’.⁶ To imagine Black Power with trans liberation at its centre is a decolonial act.

Scholar and writer Rinaldo Walcott argues that ‘Black freedom is not just freedom for Black subjects’ because it ‘would require global reordering, rethinking, remaking’, that ‘would mean a reorientation of the planet and all modes of being human on it’.⁷

The ways that we are able to exist as Black people and trans people have been shaped by systems of whiteness. For embodiment to be possible, we have to be able to imagine it outside of a white colonial framework.

Here, ‘trans’ refers to transgender. As a methodology it makes space outside of rigid binaries, imagining beyond the structures we have previously known. One of my collaborators, artist and community organiser Levi Appleton, says that ‘trans can mean movement, but it can also mean space’. To be trans is a way of taking up space in an embodied state.

In trans and Black communities, and those at the intersections of these identities, naming can act as a form of embodiment. Whereas ‘deadnaming’ is – intentionally or unintentionally – ‘[r]eferring to a transgender person by their birth name, even after they have specified their chosen name’.⁸ Often researchers will deadname figures in the archives. A starting point for my trans methodology was the decision to not deadname individuals included in this history, regardless of gender identity. Where birth names are included in archival documents, I am using asterisks in my work to indicate that I have used a chosen name. For example, *Pauulu Kamarakafego*.

Small acts of embodiment can be considered as part of future world building – bringing the world and selves into existence that we are visioning outside of white supremacist, heteronormative modalities.

Trans-cribe & Trans-late

My research process involves using archival documents, both typed and handwritten. I photograph, and in some cases, transcribe each document. Although transcription cannot retain the materiality of the document, it allows for a more accessible version of the record. The handwriting in the documents is at times completely illegible. The records include handwritten corrections and are in places heavily redacted. The existence of these documents in The National Archives could be seen as investing them with authority. However, in this work I am critical of the state’s voice – the conversations that it has with itself that bolster the motivations for their operations. I am translating these documents into my painting, finding ways to include the messiness, the ways that the history feels incomplete and overwhelming.

Anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues that ‘the presences and absences’ that can be found in the archive ‘are neither neutral or natural. They are created’.⁹ Using a trans methodology within archival research also calls into question the structures of the archive itself. That is, the categorisation, taxonomies and descriptions designed to fit history into systems of knowledge and power. History cannot, however, be contained into such a vessel. Categorisation demands choices to be made based on human-designed hierarchies and identifiers, prioritising one aspect over another. Disentangling this requires examining every aspect of these materials, not just their content, but also the ways they have been contained and why.

Building upon my methodology, Black Atlantic Museum offered the provocation to consider ‘trans’ as prefix. This has been a useful way to surface the different elements of my research.

Trans-mitter

Through painting and drawing I translate and juxtapose the voices of the British government with those of Black activists. The archives reveal that British officials viewed Caribbean Black Power groups as ‘extremists’, and hoped to exploit any potential differences between activists and more moderate community members through the use of propaganda.10

On the other hand, the Manifesto of Bermudian group the Black Beret Cadre paints quite a different picture by highlighting a desire for community-led infrastructure and resources. The Black Beret Cadre ask what if the ‘gossip circles suddenly became centers [sic] of information for the revolutionary forces’?11 In my painting The Gossip Circle(2022), I envisage what these desires could have looked like if they had been fully realised. The gossip circle is a space stereotypically associated with the feminine. This painting visualises a space associated with the feminine, where care is shared: where you get your hair done sitting between someone’s legs, where aunties whisper freely. In this work, hair and children act as transmitters, disseminating concealed information. Children as message-bearers feature as a theme continuing into other works. In another painting children, who are semi-hidden, run through the background. This is in direct opposition to the British officials and their collaborators who use concealment as a tactic to hold power.

Chronology of Independence in the English-Speaking Caribbean

Jamaica 1962

Trinidad 1962

Guyana* 1966

Barbados 1966

Bahamas 1973

Grenada 1974

Dominica 1978

St. Lucia 1979

St. Vincent 1979

Antigua and Barbuda 1981

Belize* 1981

St. Kitts and Nevis 1983

*Guyana and Belize have been included although they are geographically on the Central and South American mainland, as they are included in this history of Black Power in the English-speaking Caribbean.

Existing British Caribbean Territories

Anguilla

Bermuda

British Virgin Islands

Cayman Islands

Montserrat

Turks and the Caicos Islands

Trans-gression

At the turn of independence, a sense of national identity was being promoted by newly elected Caribbean governments. Flags were designed and national mottos drafted to reflect a sense of nationhood. Yet, some of the laws inherited from the British Empire remained. Anti-gay laws and binary gender restrictions introduced under colonial rule remain in some independent nations as a condition of Empire. In recent years, a number of anti-gay laws have been challenged in Caribbean countries, to rule them as unconstitutional, with some success.12

Within ‘imperialist white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy’13 to be Black, trans, or Black and trans is transgressive. To name these modalities of transgression, writer and gender theorist Kate Bornstein and Leslie Feinberg refer to ‘gender outlaws’ and ‘social outlaws’, respectively.14 The ways that Blackness and gender non-conformity are still treated as transgressive are visible through how British conservative politicians’ attempt to gain favour with right-wing supporters by rolling back trans rights;15 through the policing of Black people in UK public spaces;16 and in the number of trans (and especially Black trans) women murdered on a global scale.17

The Black Beret Cadre articulated an intersectional perspective on how gender and race-based forms of oppression are inextricably linked. In their Manifesto, they urged that, inherent in Black women’s experiences are ‘fundamental questions of colonialism, capitalism and oppression’. They also claimed that ‘Black women suffer oppression, not only because they are women but also because they are Black’.18 The Cadre were considered ‘a serious threat’ by the British government.19 One element of this perceived danger was in the potential for the Cadre to gain support from the wider Black community in Bermuda.

However, the aim of this research is not to rewrite history. Rather, this trans methodology imagines what could have been possible for Black activists like the Black Beret Cadre, if they had an environment to flourish in outside of colonial notions of gender. It is also not a stretch to think of this as feasible. In 1970, the same year that the Manifesto was written, the Black Panther Party’s Huey P. Newton wrote an open letter calling for solidarities between the Black Power movement and the women and gay liberation movements.20

A trans methodology makes space to exist outside of binaries, including a binary and linear reading of history. I am taking elements from history and pose the following question: ‘what does it mean when these moments – women and gay liberation, and Black Power – are brought together? What happens when history is (re-)framed by this context?’

Trans-Atlantic

In the late 1960s and early 70s, networks of Black activists across the Caribbean were striving for radical social change, often directly resisting local governments. Black activists were shaping a Caribbean Black Power movement. Yet, the history of Black Power cannot be neatly contained into geographical locations either. Movements were interwoven, with activists such as Kwame Ture, travelling from North America to the Caribbean, to West Africa and elsewhere. In my painting I am highlighting that at this moment, Britain was driven in its efforts to ensure that self-governance in the Caribbean involved no semblance of Black Power other than as a sanitised, neoliberal imagining. FCO records show that Britain monitored Black Power’s reception in the Caribbean and that they collaborated with U.S. and Canadian governments, creating ‘stop lists’ prohibiting known Black activists from travelling between North America and British Caribbean Territories.21

Other records highlight a palpable anxiety within the British government regarding Black Power movements and communist nations building solidarities. For this reason, unattributable propaganda was created by the Information Research Department (IRD), Britain’s ‘secret propaganda unit’, impersonating communist organisations and making racist remarks to stir racial tensions.22 The idea that we trans people try to trick cisgender people with our gender presentations is an idea often weaponised against us to roll back trans rights. Whereas, in actuality, the British government has repeatedly used deception, concealment and impersonation as tools to maintain control and power.

Trans-historical

The importance of this work is in contextualising the FCO records in the drive to address British colonial legacies. Rather than an isolated moment, Britain’s response to Caribbean Black Power organising is one thread in a tapestry of continued attempts to hold power. Despite the dominant narrative of the withdrawal process leading to independence, Britain extended its influence to suppress Black Power, thus deciding which forms of freedom were acceptable and which were not.

Rinaldo Walcott articulates that attempts to claim Black freedom have been ‘undermined and violently interdicted’ in the U.S. through ‘the surveillance and infiltration project of the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) and, more recently, the agency’s creation of the “Black Identity Extremist” designation to apply to Black activists’.23 This mirrors tactics employed by the British government to suppress Caribbean Black Power movements, as well as contemporary iterations such as Black Lives Matter UK. My research contextualises Caribbean Black Power movements into a larger genealogy of Britain’s attempts to interdict Black embodiment as it sits outside of a neoliberal imagining.

The growth of youth-led Caribbean Black Power movements triggered a trepidation within the British government. In 1970, the British High Commissioner to Jamaica, E.N. Larmour, wrote that ‘…there has been considerable growth in Black Power feeling in the secondary schools’. Also, he continued, ‘The increased sympathy for Black Power among senior school pupils is likely to mean a new influx of potential Black Power supporters to the University in the next year or two’.24 In Jamaica there was little British officials could do overtly in reaction to this, other than to advise the then Jamaican Prime Minister, Hugh Shearer.

Whereas in British Territory Bermuda, Quito Swan notes, a propaganda campaign was launched by the IRD against the Black Beret Cadre. Indeed, the historian emphasises that the increase in youth-led organising in Bermuda ‘reflected the embracing of the Movement by youth across the Caribbean’.25

I speculate that the strategies used in reaction to Caribbean Black Power movements laid the foundations for future British operations, both in the Caribbean and the UK. After the largely youth-led Black Lives Matter protests and the toppling of the Edward Colston statue in 2020, the Department for Education released the ‘Plan your relationships, sex and health curriculum’ guidance. The guidance stated that schools should not promote ‘victim narratives that are harmful to British society’.26 Author, educator and activist Camille London-Miyo writes that it also prohibited ‘educators from using any material which fails to condemn illegal activities or supports violent actions against people or property’ and that this meant that ‘actions like the pulling down of the Edward Colston statue or the poll tax riots of the 1980s could not be discussed by young people’.27 In 2021, the British government went one step further, introducing the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill; increasing restrictions on the right to protest and heavily criminalising actions to remove statues. Additionally, in 2022 Conservative MP Rishi Sunak said that, in the hopes of boosting his popularity, ‘Whether it’s pulling down statues of historic figures, replacing the school curriculum with anti-British propaganda or rewriting the English language so we can’t even use words like “man”, “woman” or “mother” without being told we’re offending someone’.28 What is implicit here is that Black and trans liberation are popular bargaining tools for right-wing politicians looking to garner favour.

Trans-mute

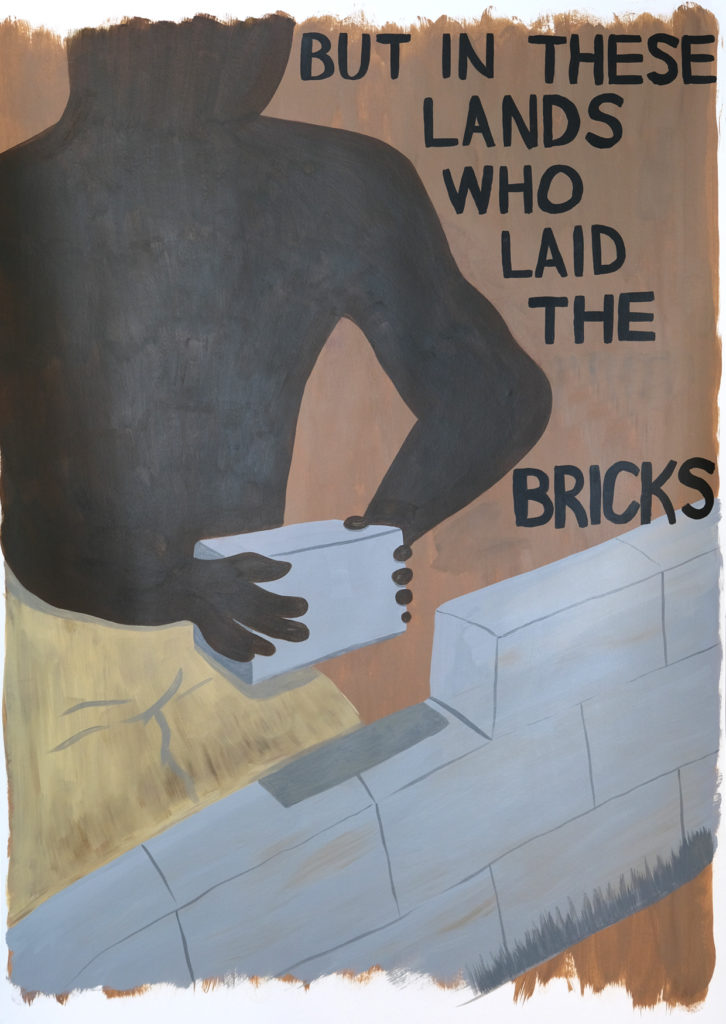

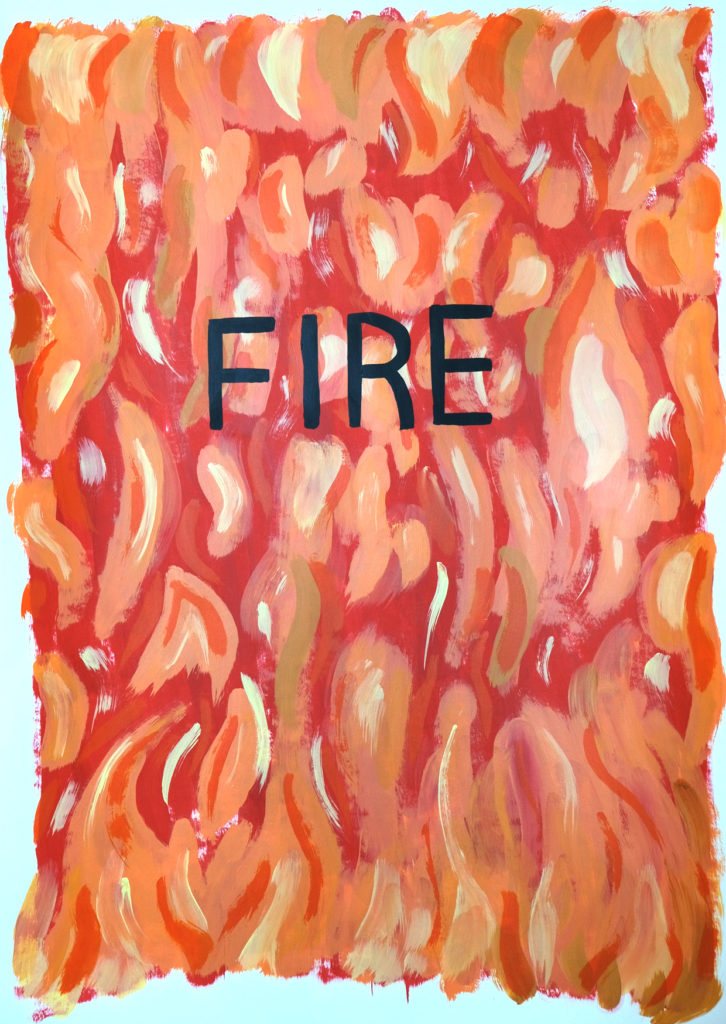

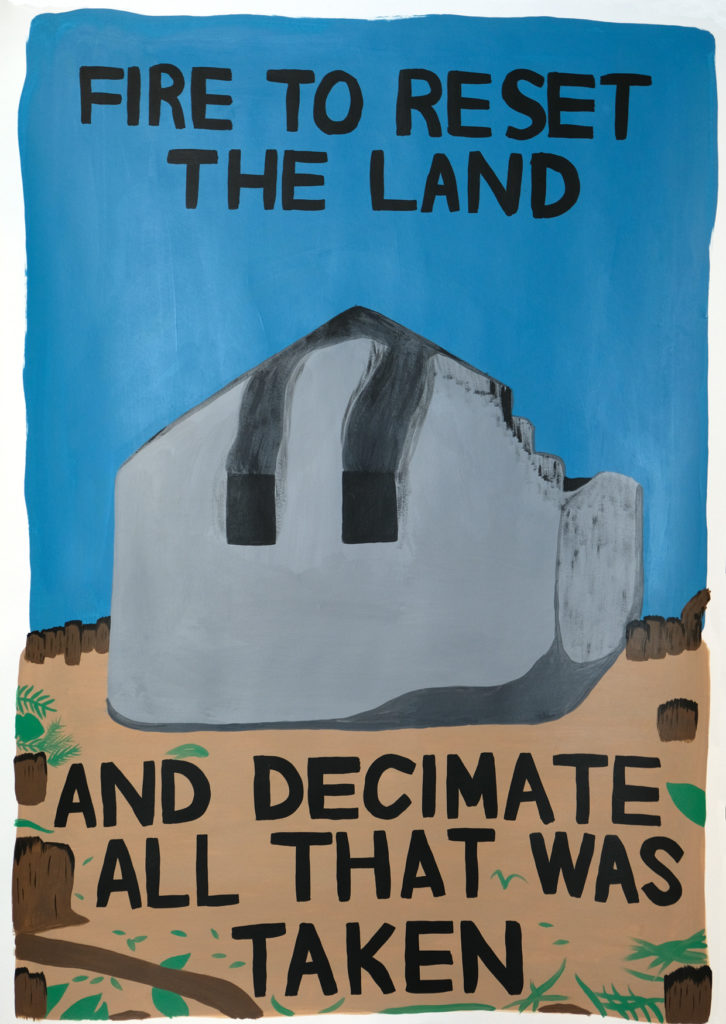

One work that seeks to thread this history into the wider narrative of colonial legacies is the series Old Devonshire Church Fire, Bermuda (2022). The starting point for this work was a record on the Black Beret Cadre, mentioning an arson attack that destroyed a church in Bermuda. British officials were keen to pin any possible charges on the Cadre. In a telegram to then Bermuda governor Lord Martonmere, A.J. Fairclough suggested as measures against Black resistance in Bermuda the ‘Removal of especially obnoxious leaders from circulation by deporting and stop-listing non-Bermudians and special effort to secure convictions (leading to significant terms of imprisonment) of offending Bermudians’.29

In this series, I consider what Walcott describes as ‘glimpses of Black freedom’.30 This includes the autonomy to decide what does and does not belong in a decolonial landscape and brings into question who built the church in the first place. The series combines text and image to explore the idea of fire as a means of anti-colonial resistance, referencing the history of enslaved Black people setting fire to plantations. The works aim to connect these moments in history – the burning of the church and plantations – highlighting that sometimes fire is the only tool available in the face of colonial power.

Black resistance movements are heterogenous in nature, and Caribbean Black Power was no exception to this. Although a collective goal was autonomy for Black people in countries where this had never been fully experienced, this took various forms in practice. Black activists attempted to create a network across the Caribbean, making space for Black Power’s amorphous shape in the region.

British officials surveilled the ways that Black Power took form in the Caribbean, regarding the level of threat this represented in various locations.31 They acknowledged that they could not stop Black Power from transmutating; however, they stated, ‘its evil influences can, and must be, retarded’.32 Through IRD propaganda they attempted to dilute Black Power’s message and spread animosity where possible between activists.

Conclusion

As I continue this research, I hope that by working outside of binaries, I can offer pieces of this incomplete puzzle. I also ambition to make space for the incongruent voices included in this history, inviting others to reassess those fixed and finished narratives that become cultural stalwarts. A question that still sits with me is ‘how can I examine the contents of the archive without replicating its’ structures and power?’ I hope that by translating these archival documents into my visual practice, placing them in proximity to other voices, there will be room for new conversations and imaginings.

- 1. Kara Keeling, Queer Times, Black Futures, New York: New York University Press, 2019, p.69.

- 2. Eric A. Stanley & Nat Smith (ed.), Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, Edinburgh, Oakland, Baltimore: AK Press, 2011, p.5.

- 3. C. Riley Snorton, Black On Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity, Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017, p.2.

- 4. Louis Lindsay, The Myth of Independence: Middle Class Politics and Non-Mobilization in Jamaica, Mona, Jamaica: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies, 1975, p.94.

- 5. The National Archives is both the repository and the organisation acting as gatekeepers of the history. The records from the Information Research Department were migrated to The National Archives during 2018-19, however they are accruing and being released in batches. Where records include reports from other departments within the FCO, parts of the record may have been available prior to 2019.

- 6. Leslie Feinberg, Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink or Blue, Boston: Beacon Press, 1998, p.6.

- 7. Rinaldo Walcott, The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Black Freedom, Durham: Duke University Press, 2021, p.5.

- 8. Clémence Michallon, ‘Let’s talk about deadnaming trans people and why ‘freedom of speech’ isn’t always the answer’, Independent[online], 26 June, 2019, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/transgender-deadnaming-imdb-birth-name-chosen-why-a8976601.html(last accessed on 9 September 2022).

- 9. Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Boston: Beacon, 2015, p.50.

- 10. The National Archives of the UK (TNA): FCO 168/3893, 17 May 1969 Correspondence from unknown author to Elizabeth Allott. ‘Information Research Department: Black Power Conference, Bermuda, July 1969; proposed operations’.

- 11. TNA: FCO 168/4508, 1971. ‘Information Research Department: Black Power; Black Beret Cadre; Manifesto’.

- 12. Gemma Handy, ‘Antigua’s ban on same-sex acts ruled unconstitutional’, BBC [online], 6 July 2022, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-62068589 (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 13. Quoted by journalist Amy Goodman in ‘Black Feminist bell hooks’Trailblazing Critique of “Imperialist White Supremacist Heteropatriarchy”’, Democracy Now! [online], available at https://www.democracynow.org/2021/12/17/bell_hooks_legacy_beverly_guy_sheftall (last accessed on 2 September 2022). Feminist and critical race theorist bell hooks uses this expression to describe systems that govern our lives.

- 14. Kate Bornstein, Gender Outlaw: On men, women and the rest of us, New York: Routledge, 1994; L. Feinberg, Trans Lib, op. cit., p.10.

- 15. Gaby Hinsliff, ‘The PM sees votes in a culture war over trans rights, but this issue must transcend party politics’, The Guardian [online], 13 April 2022, available at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/apr/13/local-elections-tories-culture-war-trans-rights-conversion-practices (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 16. Andre Rhoden-Paul, ‘Stop and search: Ethnic minorities unfairly targeted by police – watchdog’, BBC [online], 20 April 2022, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-61167875 (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 17. Jamie Wareham, ‘375 Transgender People Murdered In 2021 – “Deadliest Year” Since Records Began’, Forbes [online], 11 November 2021, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2021/11/11/375-transgender-people-murdered-in-2021-deadliest-year-since-records-began/ (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 18. ‘Information Research Department: Black Power; Black Beret Cadre; Manifesto’, op. cit.

- 19. TNA: FCO 168/4086, 17 April 1970 Report by A.J. Fairclough to J.C. Morgan. ‘Information Research Department: Black Power’.

- 20. ‘Solidarity with the Black Panther Party’, The Berkeley Revolution. A Digital Archive of the East Bay’s Transformation in the Late 1960s & 1970s [website], available at https://revolution.berkeley.edu/solidarity-black-panther-party/ (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 21. TNA: FCO 168/3721, 24 June 1969 Report by L.S. Price to A.J. Fairclough. 'Information Research Department: visits abroad by IRD representatives; Black Power Conference, Bermuda, July 1969’.

- 22. See: Sanchia Berg, ‘”Fake news” sent out by government department’, BBC [online], 18 March 2019, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-47571253 (last accessed on 2 September 2022); Jason Burke, ‘Secret British “black propaganda” campaign targeted cold war enemies’, The Guardian [online], 14 May 2022, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/14/secret-british-black-propaganda-campaign-targeted-cold-war-enemies-information-research-department (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 23. R. Walcott, The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Black Freedom, op. cit., pp.1 and 6.

- 24. TNA: FCO 63/492, 1970. ‘First impressions of E N Larmour, the newly posted British High Commissioner to Jamaica’.

- 25. Quito Swan, Black Power in Bermuda: The Struggle for Decolonization, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 91.

- 26. ‘Plan your relationships, sex and health curriculum’, 24 September 2020, available at https://www.gov.uk/guidance/plan-your-relationships-sex-and-health-curriculum (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 27. Camille London-Miyo, ‘I didn’t become a teacher to ban independent thought. Anti-racist education should not be up for debate’, Independent [online], 1 October 2020, available at https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/education-dfe-schools-victim-narratives-capitalism-blm-racism-b737415.html (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 28. Sophie Wingate and Bill McLoughlin, ‘Rishi Sunak vows to tackle “woke nonsense” in a bid to revive leadership campaign’, Evening Standard [online], 29 July 2022, available at https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/rishi-sunak-woke-liz-truss-tory-leadership-conservative-party-west-sussex-b1015659.html (last accessed on 2 September 2022).

- 29. TNA: FCO 168/4086, 1970 Telegram from A.J. Fairclough to Lord Martonmere. ‘Information Research Department: Black Power’.

- 30. R. Walcott, The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Black Freedom, op. cit., p.2.

- 31. TNA: FCO 168/7117, 1974. ‘Information Research Department: IRD publication; [Survey of] Black Power and Radical Groups in the Commonwealth Caribbean’.

- 32. TNA: FCO 168/4086, 17 April 1970 Report by A.J. Fairclough to J.C. Morgan. ‘Information Research Department: Black Power’.