I come from a working family; I grew up without books, knowing nothing but the music danced to in neighborhood parties or the singing that accompanies work. My idea of a museum was the one that stuck with me when my school organised an excursion to the Natural History Museum: a museum holds objects from an extinct culture, tells stories of the past, I told myself. I heard about contemporary art for the first time as an adult, and I would occasionally go to exhibitions by well-known or recommended artists, most of them white men belonging to the bourgeoisie. Most of my relationship with the art market was based on indifference. I can say with certainty that I am nothing more than a dilettante neophyte in the field. So, upon the invitation to say something about it, I ask myself: what does a person like me, coming from the ‘underworld’, from the ‘uneducated people’, have to say about art? I think that maybe I shouldn’t say anything: shutting up would be my biggest contribution. I would be abandoning the task with dignity.

But then I read Anzaldúa, who broadened my perspective:

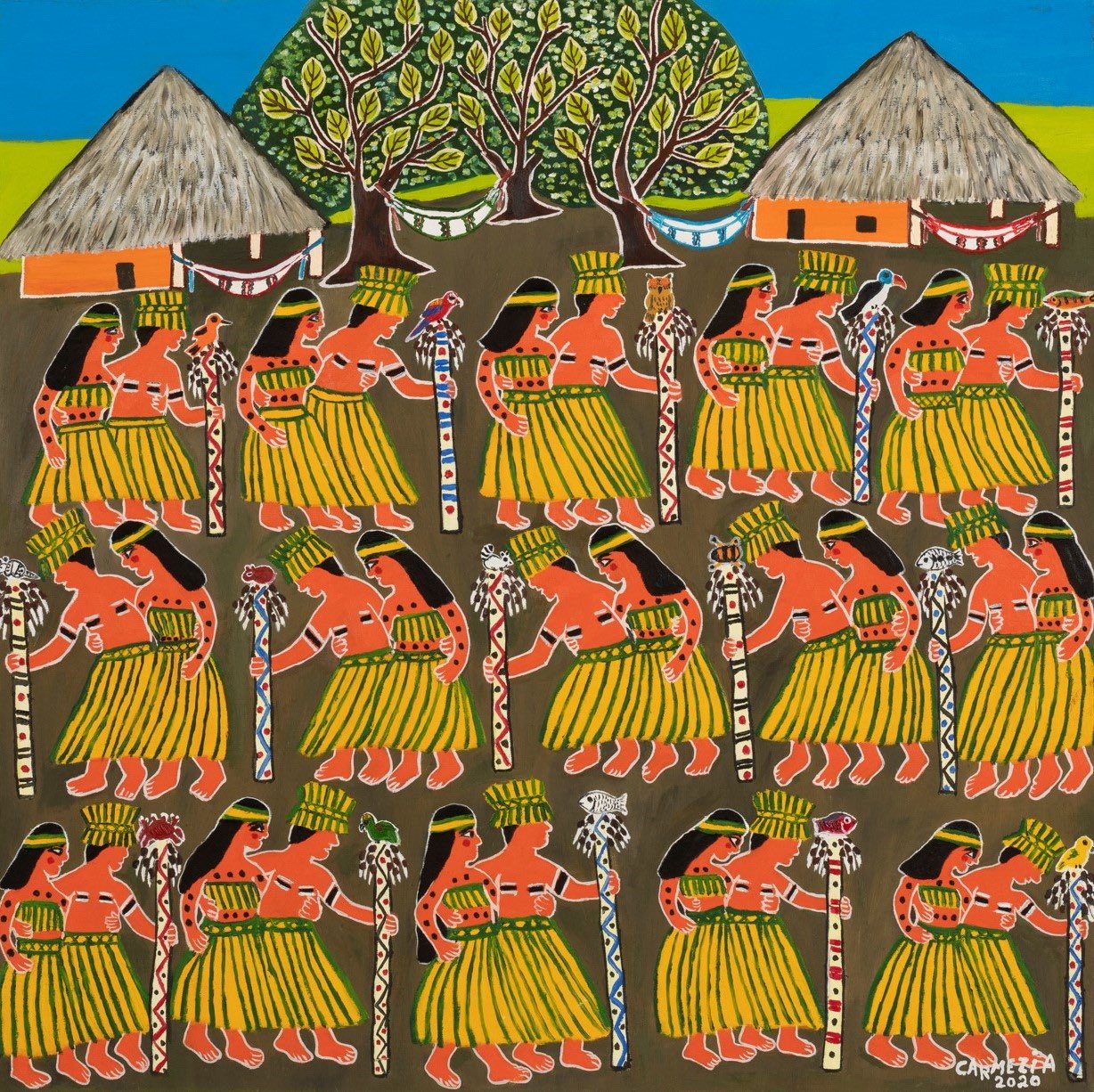

In the shaman’s ethnopoetics and performance, my people, the natives, did not separate artistic from functional, sacred from secular, art from everyday life. The religious, social, and aesthetic ends of art were all intertwined.1

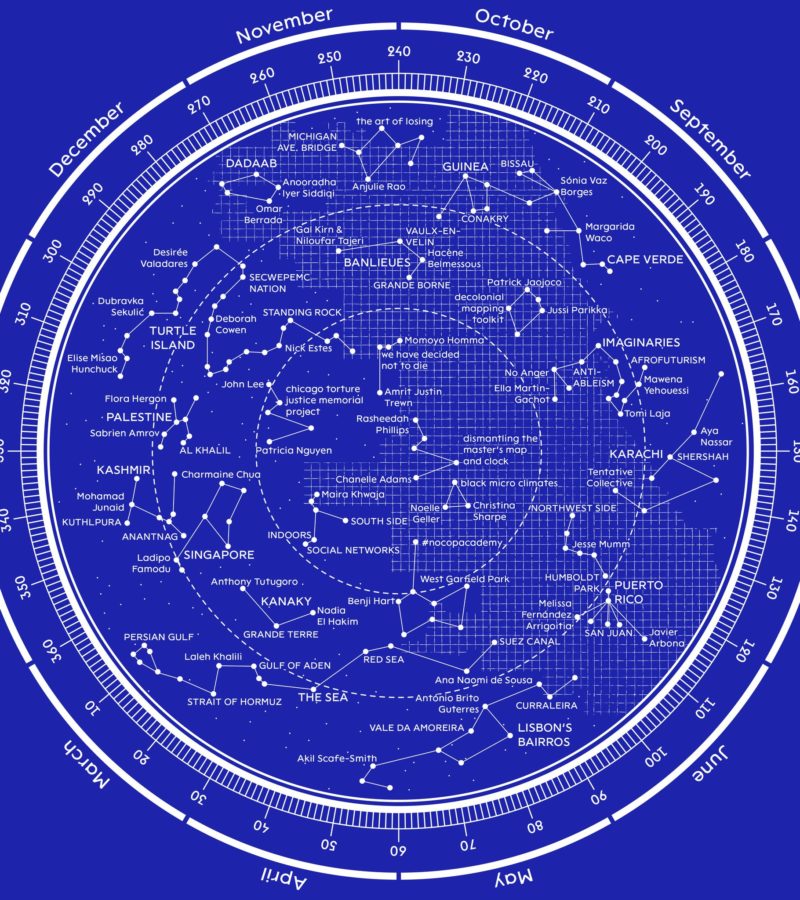

Her words echo in me, raising questions and prompting reflections on art from a decolonial perspective: what place does art occupy within decolonial policy and practice? More importantly, how does a decolonial (im)posture challenge Western interpretations of art? Besides the perspectives to which we are accustomed, what implications would a decolonising artistic practice have on what is understood as the artwork itself, its relationship with the environment, its circulation, the role of art, and the artist’s figure? Is it possible to think of art as a collective experience and as the ability to recreate and sublimate the world present in every culture, in every way of experiencing existence?

Anzaldúa reminds us of a communal order that existed before modernity: everything is intertwined. The link between living beings and between the different tasks of reproducing life and re-creating the world has not been broken. There has been no separation between thinking, feeling, acting and aesthetic experience – sensation, perception and sensitivity to everything around us.

In contrast, Western modernity brings about the separation of life into different, specialised spheres. What was once united are now separate areas of specialisation, which are occupied by specific subjects who develop their work in specific places. The sphere dedicated to the formation of new generations gives way to pedagogy, and the School appears as a place between walls dedicated to training and specialisation in areas of knowledge that are also themselves separate and well differentiated from each other. The production of knowledge gives way to epistemology and a scientific method that requires a specific, unobserved and uncontaminated place for its development: the laboratory, the academy and the research institutes must be dedicated to it, while all other ways of knowing are devalued and delegitimised. Aesthetic production and creative capacity give way to art as a differentiated sphere, with specific subjects constructed as possessing a superior sensitivity, a capability of producing beauty. In the eighteenth century, this sphere constructed a scenario for its own development and circulation, as museums appeared for the first time.2

According to Zulma Palermo, the coloniality of art has been well established since the beginning of the conquest of Abya Yala, when the colonial enterprise, denying native cultures, sought:

[…] to erase the traces of the ways of learning and transmitting techniques and the use of materials specific to the habitat, replacing them with the perspectives, instruments, and materials of their own, superior and advanced civilization. Since that first contact […] the aesthetic criteria that are put into circulation will prevail.3

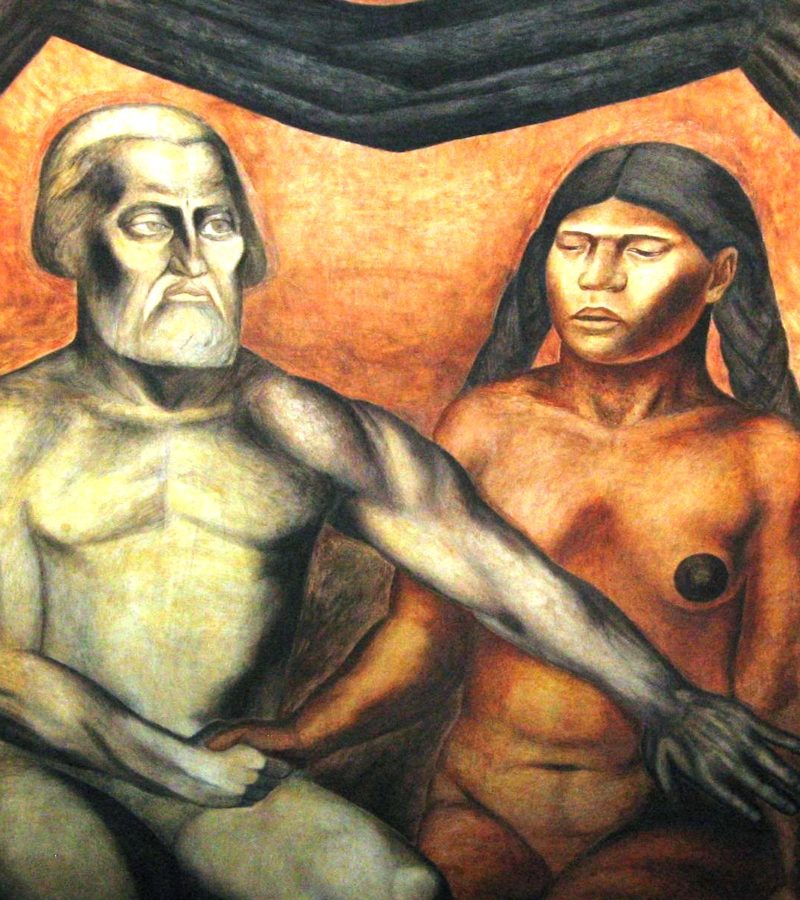

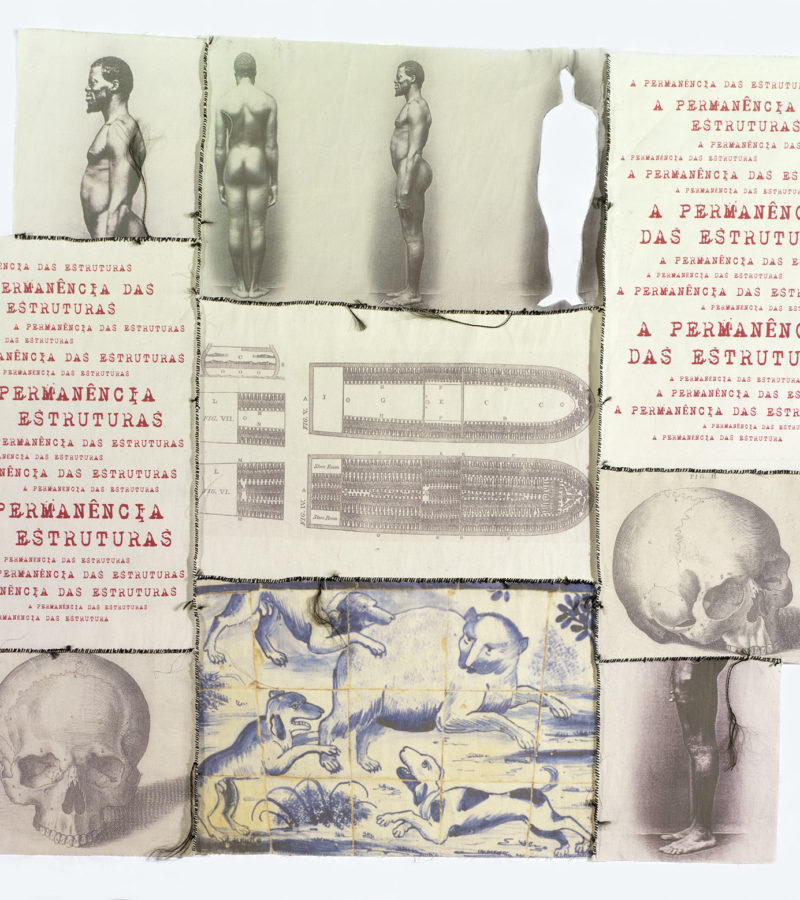

From that moment on, the criteria used globally to validate some works as artistic and others as ‘handicraft’ or ‘folklore’ would be imposed and conformed to. Through its modern/colonial project, the West has established and imposed the guidelines of what can be considered as art. According to these criteria, the artistic work has a higher aesthetic value insofar as it appeals to universality. Meanwhile, other modes of creativity and recreation in the world have a lower value due to their communitarian and local practice, linked to other spheres of reproduction of life. For Alban Achinte (2009), this operation implied disrupting extra-European societies ‘in their cosmogonies, productive forms, food systems, ways of representing and organizing themselves, to impose a logic of existence based on the pyramidal hierarchy generated by skin color’.4 He speaks of a ‘chromatic of power’, which has endured over time and produced a model for the representation of colonised subjects that prevents them from representing themselves.

More than preventing self-representation, I believe that the colonial enterprise has hindered the autonomous development of colonised subjects by intervening in their practices of production. If Europe needed to produce the racialised colonial subject to see itself as superior, colonised subjects have, since this representation’s genesis, revealed themselves in multiple and collective ways. Faced with attempted domination, colonial subjects seek to recover their agency, voice and representation of themselves, a self-representation that restores their dignity. This includes small everyday acts, armed uprisings and creative and symbolic works of self-representation. Even if they do not abandon Western representations of themselves altogether, they intervene and constantly boycott them.

Hourya Bentouhami, a postcolonial philosopher of Arab origin,5 renews criticisms levelled by racialised women at ‘mainstream’ feminism – with its Eurocentric bases and commitment to modernity/coloniality – by proposing a ‘feminism of marronage.’ She takes up the idea of ‘marronage’ as the act by which the enslaved person escapes from a plantation, from slavery and settles in a new territory, where they can re-found a community (and themselves) among equals, that is, with other Black people, but also with Indigenous and racialised people of the world.

I invoke the idea of marronage in its symbolic and material sense rather than as an exceptional act that the subject condemned to the place of non-being performs, leading to their eventual liberation ‘once and for all’. I allow myself to propose marronage as an interventional methodology for the oppressed and an epistemic apparatus that always boycotts and interrupts the dominant racist discourses’ attempts to capture them and represent them as Other – as non-subjects. In the end, ‘the visual machinery of racialisation that accompanied the development of modern/colonial capitalism’ failed to exterminate, or to successfully and definitively confine, the creative capacity and symbolic production of the subalternised.6

To the ‘colonial panoptic gaze,7 and its attempts to classify, control and cannibalise native groups, as well as those trafficked between continents, we propose an aesthetic/symbolic marronage as a ‘methodology of the oppressed’.8 For decades now, critical reason has called for an urgent and imperative epistemic disobedience within cultural studies and artistic production. It would, however, be a mistake to restrict these acts of sabotage to fields that – even if they contain spaces for criticising modernity and the global capitalist flows of art consumption – remain subject to guidelines produced by the West regarding what deserves to be considered as an artistic work or even as critical art.

Naturally, we should celebrate aesthetic interventions that seek to produce works and cultural products that interrupt the visual economies of Otherness circulating in the global art market. Yet, it would be wrong not to contemplate individual and collective creations that are part of othered communities’ intangible cultural collections. These productions represent ways of doing that ensure reproduction and continuity of life and the communal bond, being a greater expression of the ability to create and symbolise that is possessed by every people, including those to whom we have denied or among whom we have attempted to erase such capacity. I propose to think about maroon aesthetic practices of concealing the colonial narrative and visual regime in ways that are not always, nor necessarily, conscious forms of resistance, but which are above all immanent forms of preserving and celebrating life and expressing the potency of existence.

In short, this is about seeking and following the clues that allow us to find out how other visual regimes and epistemologies frequently produce escapes or fissures in the narratives and aesthetic representations fabricated by the West. These acts of maroon production, or rather, this aesthetic/symbolic marronage, have always existed and have been an inexhaustible source of representation of oneself and the world. Although we can find much of the Western gaze applied to ourselves in it, it is also a methodology of neutralisation, intervention and subaltern disruption that ambushes the world’s senses as proposed by Eurocentrism.

According to Mayan artist Eduardo Camey:

The different modern institutions, including art and culture centers, have reaffirmed concepts, categories, and discourses about art and culture that put rational thinking as the only valid, universal, and legitimate one. […On the contrary,] decolonial aesthetics are a way of becoming aware of the place we inhabit in the power matrix, of the assumptions of control around subjectivities – around art. It means, then, to retake, embrace and live the patän samaj shared by our grandparents, from antiquity to our days.9

I would like to conclude these reflections by pointing out that, despite the space given in museums to contemporary interventions by artists from the worlds discarded by modernity; and despite the space given to interventions by feminists, women, and non-normative identities of gender and sexuality, the task of decolonising the art field is incipient, and much remains to be done. Following the warnings of Anzaldúa and artists from ancestral territories who call for decolonisation, it implies jeopardising the very existence of this field, separated from life and daily actions, to which creative and creating work has been condemned. I venture to affirm that the act of opening the museum’s doors to the condemned of the world is not enough. In the end, the task means questioning the field’s very existence as a space separate from life. Decolonisation implies the radical gesture of dynamiting this specialised space, these four walls that have hijacked art as interpretation, imagination, symbolisation and recreation of the world. It means abandoning the museum as a cemetery of dead objects, secluded from what gives them meaning and transcendence. It is, above all, a radical questioning of art’s commodification as an evil that continues to reproduce the critic’s disease, still present in feminist art interventions, the reception of which remains in the hands of those more privileged – and in much of the marginal art developed by Indigenous and afro-descendant artists.

How to restore art to its sacredness? How to place art in relation to the world that gives it meaning so as to return it to a situated sensitivity? These are crucial questions that arise when we relate to art beyond the Eurocentric understanding that we have grown used to. To paraphrase Anzaldúa, the task of decolonisation invites us to stop ‘importing Greek myths and the split point of view of Western Cartesianism’ and to take root in the mythological soil and soul of the land that sustains us.10

- 1. Gloria Anzaldúa, ‘Borderlands/La frontera: la nueva mestiza’, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, University Program in Gender Studies, 2015, p.120.

- 2. Walter Mignolo, ‘Prefacio’, in Zulma Palermo: Arte y estética en la encrucijada descolonial (comp.), Buenos Aires, Editorial del Signo, 2009.

- 3. Zulma Palermo, ‘Introducción’, in Zulma Palermo (op. cit.) p.17.

- 4. Adolfo Albán Achinte, ‘Artistas indígenas y afrocolombianos: entre las memorias’ in Zulma Palermo (op. cit.) p.84.

- 5. Hourya Bentouhami, 'Notas Para un Feminismo Cimarrón: Del cuerpo-doble al cuerpo propio', in Revista Madrigera Violeta, 2018.

- 6. Joaquín Barriendos, ‘La Colonialidad del Ver. Hacia un Nuevo Diálogo Visual Interepistémico en Regímenes de Visualidad: emancipación y otredad desde América Latina’, Revista Nómadas no.35, Bogotá: Instituto de Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos, Universidad Central, 2011, p.26.

- A concept proposed by Iris Zabala and taken up by Joaquín Barriendos to refer to the ‘visual rhetoric about cannibalism in the Indies', (op. cit., p.16.)

- Chela Sandoval, ‘Nuevas ciencias: feminismo cyborg y metodologia de los oprimidos’, in: hooks, bell; Brah, Avtar; Sandoval, Chela; et al. Otras Inapropiables: feminismos desde las fronteras, Madrid: Editorial Traficantes de Sueños, 2014, pp.81–106.

- Eduardo Camey, ‘Kaxlan na’oj – wakamin na’oj chuqa’ ch’ajch’orisanem pa junamil na’oj: Colonialidad-modernidad y estéticas decoloniales en un mundo globalizado’, in Movimiento de Artistas Mayas: Algunas palabras sobre el trabajo del artista maya, Sololá, Guatemala: El Tablón, 2014, p.226.

- 10. Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: la nueva mestiza, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, University Program in Gender Studies, 2015, p.123.

![[Description: Black and white photograph of people looking out of a window]](https://www.afterallartschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Thomaz-Farkas_Rahul-Rao-800x900.jpg)

![[Description: Valeska Soares, Duplaface (Branco de titânio), 2017. Oil and cutout on existing oil portrait, 71 x 56cm. Courtesy MASP]](https://www.afterallartschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Osmundo_Valeska-Soares-800x900.jpg)