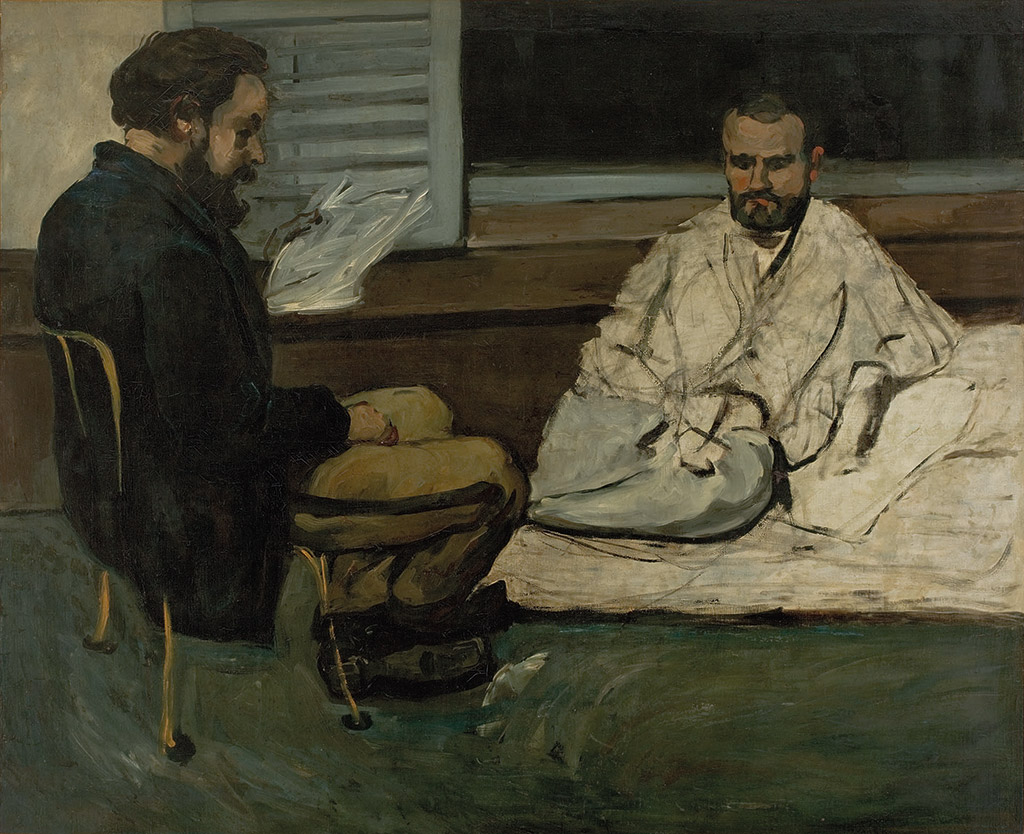

One man reads a manuscript to another who, assuming the role of teacher, evaluates what is being read. Although the teacher’s pose seems solid, his body has been formed in gestural brushstrokes that undermine the impression of firmness. As such, the painter who paints this scene with his brush is felt in his presence as a third character, no less important than the other two. The painting, held in the collection of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), is Alexis Reads a Manuscript to Émile Zola. The characters are, respectively, Paul Alexis, Emile Zola, and Paul Cézanne. Cézanne’s gestures make Zola’s body appear unfinished. Also incompletely sketched are Alexis’s hand and the paper he holds, as though what he is reading were still being written. It is as though the manuscript can only to be considered ‘finished’ upon receiving the master’s approval.

In 1927, a year after the death of Zola’s wife, the painting in question was discovered at Zola’s house in Médan.1 Cézanne had started the painting in 1869 – the same year Alexis had arrived in Paris from Aix – but abandoned it the following year on leaving the French capital due to the Franco-Prussian War.2 Also abandoned was the friendship between painter and writer. In a sense, the picture can also be viewed as a record of an interrupted friendship.

The relationship between Cézanne and Zola is well documented. The two left Aix en Provence in the mid-nineteenth century, making their way to the French capital to build their careers as painter and writer respectively. Zola did not take long to achieve success, writing articles and reviews for such important newspapers as Le Figaro and La Tribune even as a young man. While the painter was experiencing a string of failures, the writer was reaping the glories of early recognition. It wasn’t until towards the end of his life that Cézanne became recognised, notably when Ambroise Vollard started to deal his works on the French market. By 1903, Cézanne’s paintings were worth more than Monet’s, but unlike Monet, Cézanne had had to wait for old age for his art to be appreciated.

In 1866, in an article entitled ‘Mon Ami Paul Cézanne’, Zola declared that the two men’s lives had been ‘built together’.3 Years later in 1886, however, he would publish a novel that led to a definitive rupture between the friends. In The Masterpiece, Zola’s character Claude Lantier partially inspired by Cézanne, is a disgraced painter, styled (just as Zola named Cézanne) as an ‘aborted genius’. Like Lantier, Cézanne experiences numerous frustrations in life, and doubts himself throughout his career. Following the publication of the book, the painter would never again touch the canvas now in MASP with his brushes.

Let us move on to the third character in the scene. Alexis, like Cézanne and Zola, had left Aix as a young man to try life in the French capital. Contrary to his parents’ wishes, Alexis abandoned studies in law to pursue a career as a poet. On arriving in the capital, he sought out Zola in particular, hoping to be graced by his wisdom. At the time, Zola was emerging as one of the leading intellectuals of his generation. In the painting, he seems to embody the majesty of a kind of master or guru. Alexis, meanwhile, is carved into the picture with thick, dark brushstrokes. His body barely fits the vertical edges of the canvas and his back is bent as though to stay within the frame. His discomfort is visible, as if from the physical strain of showing all his reverence to Zola – leader of the group. The scene’s apparent calm conceals a tension in which the act of reading – and writing – is also an act of expectation and validation. It is the wait for recognition from the one who has achieved the greatest success of all three friends who left Aix. This is why Zola appears capable of legitimising the steps to be taken by the other two. It is possible that Zola himself wanted to be depicted in this way; he had always fuelled the claim to his status as a kind of ‘master’ of a style, and would actively gather comrades from Aix around his own leadership.

There is another picture painted in 1869, now in a private collection in Switzerland, that also brings Alexis and Zola together in the act of reading and listening. This work seems to make a clear gesture towards Dutch Golden Age painting, its scene reminiscent of the environments designed by Vermeer or De Hooch. Both characters play the same roles – student and teacher –as in the painting in São Paulo, but here Alexis holds a pen, and seems to be writing down Zola’s spoken words. Here Zola still possesses the solemnity of a teacher, but not the specific grandeur of the eastern philosopher or sage.4 Whereas in MASP’s picture, Cézanne seems to insert himself in the scene, acknowledging Zola’s leadership as the group’s mentor, in the case of the painting in the Swiss collection the painter casts himself as more of an external observer. His perspective comes from outside the room and is limited to what is revealed through an open curtain.

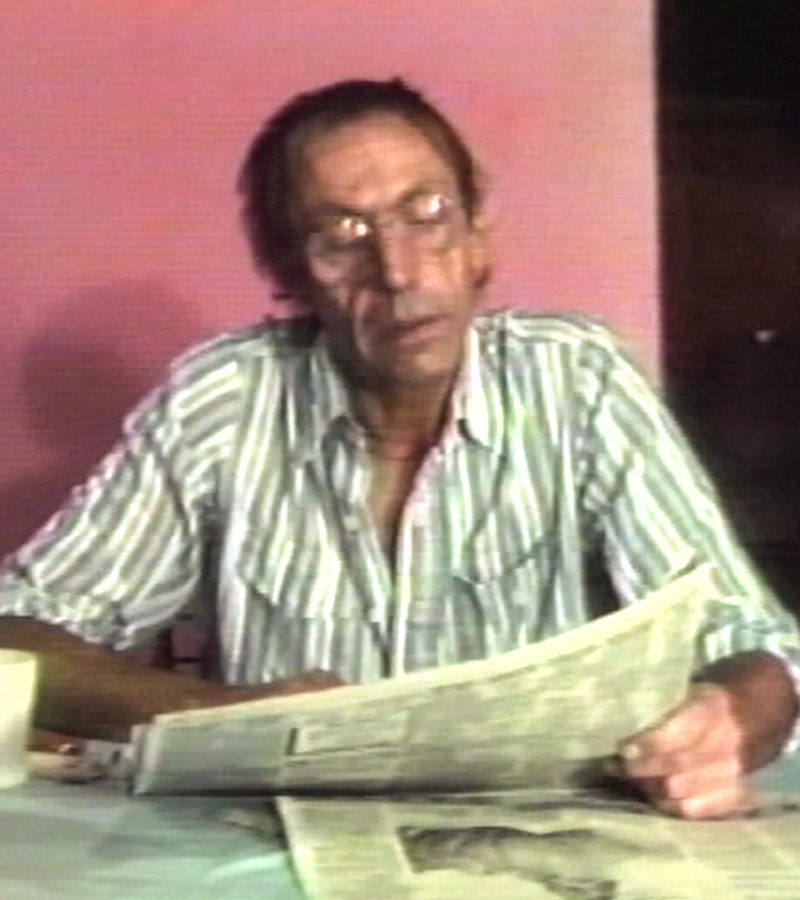

In both paintings, however, sketchy brushstrokes evoke a certain hesitation on the part of the painter when gazing at the writer. This is also the case in an earlier portrait of another authority figure – this time the artist’s father reading a newspaper. As with the others, this painting is delimited by darkened brushstrokes and depicted in tonal colours. Cézanne’s father sits in a chair that resembles a throne, but just as in Zola’s case, the object’s solidity contrasts with the delicate feet that support it. The strength inspired by the character seems to be sabotaged again by a detail that relativises it. The three paintings evoke an early stage of Cézanne’s artistic production, still a long way off from the formal research that would inspire Picasso in the early part of the following century. They bring to mind Manet, who also painted Zola as an inspiring intellectual and was defended by him in several of the writer’s articles. In any case, in both his early and final paintings, Cézanne seems to move along the canvas with a degree of hesitation. There is no detailed planning, but rather a faltering path in which the picture emerges out of a combination of doubt and discovery.

Zola was one of the leading art critics of the nineteenth century. Alongside names like Phillipe Burty, Jules-Antoine Castagnary and Ernest Chesneau, he was able to create a new vocabulary, derived from the experimental psychology of the Third Republic, that would come to guide public perception.5 Through the critical work of these writers, understandings of art shifted from a basis in interpreting traditional themes to the reading of formal aspects associated with the artist’s personality – with brushstrokes and tones interpreted according to such ideas as the sincerity of contact between the artist and nature. Art at this juncture is no longer a matter of mastering an iconographic repertoire drawn from traditional narratives, but rather a matter of educating the public’s capacity for looking through a distinct aesthetic language. Traditional subjects, such as mythology, religion and history, are no longer areas of focus; for Zola, art was no more than ‘a corner of nature seen through a temperament’. That well-known phrase alone gives context to much of the nineteenth century’s major artistic developments.

In his text ‘Mon Ami Cézanne’, Zola makes a concise comparison between writers and artists. Writers, he thinks, are more resilient than painters, who are unable to hear harsh criticism without doubting their work. At least as far as Cézanne is concerned, this judgment seems accurate. Doubts and hesitations in the creative process are frequently mentioned throughout the painter’s letters. Indeed, the act of creation was for him a long, patient, uncertain process, in which the depiction of the visible world occurred through small and hesitant touches, ‘petites sensations’. Cézanne’s insecurities prevented him from mirroring Zola’s courageous public stance, which guided the path of younger people like Alexis and saw the writer both engage in public clashes with artists and involve himself in such controversial political matters as the Dreyfus affair. The painter, by contrast, worked apart from society – a recluse for whom the only certainty was doubt. It is not by chance that Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s famous essay on the artist, in which the painter’s approach to reality is explained as a faltering search for the real world, is called ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’.6

Merleau-Ponty argues that Cézanne’s paintings are built through a process of hesitation and continuity, with no assurances about where to go. A kind of walk on a dimly lit road where uncertainty gives way to intuition. The philosopher argues, however, that this insecurity – a kind of doubt concerning not only the objects of reality but also the artist himself – is in fact an important means of the discovery of space. The movement of the brush is marked by a productive kind of doubt that refuses to accept preconceived ideas of nature, reality and perspective, and that is capable of creating something that does not exist until it is painted.

Let us return to the MASP painting. In it, the contrast between Cézanne’s doubts and the assertive posture of Zola – a teacher who evaluates and corrects – could not be more significant. In Zola, we find confidence, in Cézanne, doubt. It is curious that it is nevertheless the writer’s body that remains unfinished in the picture, suggested by approximate brushstrokes that reveal the process of trial and error, a testimony to the painter’s way of seeing. If Zola’s assertiveness was responsible for educating the public of his time to appreciate art, Cézanne’s hesitation also guided the visions of an entire generation of artists that followed him in the early twentieth century – artists including Picasso and Matisse, who gave form to some of the most influential movements in modern art. Cézanne teaches us that to doubt is also to learn.

- 1. For more on the painting see Maria de Fatima Morethy Couto, Cézanne no Masp, Campinas, SP, 1993, and Camesasca, Ettore, De Manet a Picasso: tresors du Musee d'art de São Paulo, Milano: Martigny; Mazzotta: Fondation Pierre Gianadda, 1988.

- 2. See E. Camesasca, op. cit. p.86.

- 3. Émile Zola, ‘Mon Salon, Mon Ami Cézanne’, L’Evénement, 20 April 1866.

- 4. Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Catalogue of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, São Paulo: Prêmio, 2008, p.112.

- 5. For more, see Nicholas Green, ‘Dealing in Temperaments: Economic Transformation of the Artistic Field in France during the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century’, Art History, 10 March 1987.

- 6. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘Le Doute de Cezanne’, Fontaine: Revue mensuelle de la poesie et des lettres francaises, 6 December1945, pp.80–100.