From early June to July 2024, I spent 80 hours in the British Pavilion of the 60th Venice Biennale, invigilating John Akomfrah’s exhibition ‘Listening All Night to the Rain’. The artist was commissioned to represent the UK for the Biennale. I, along with 65 other fellows, was also selected by the British Council to represent the UK, but as an ‘exhibition ambassador’ in the pavilion. In my application for the fellowship, I mentioned my academic background in Black Studies and environmental humanities that relates to Akomfrah’s work. I also included my biographical background as a multilingual Chinese national with a diasporic living experience across the Pacific and the Atlantic who recently relocated to the UK – a subject that would fit well on Akomfrah’s screens and help the British Council fulfil its institutional requirement under the Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion framework. I was very aware of what the intersections of my identities represent, and how these could feed into the ‘representation of the UK’ that the British Council envisioned us fellows to perform, along with John Akomfrah and his work.1

Despite the use of the elevating word ‘ambassador’, the type of representation I was asked to perform was certainly not equivalent to that of Akomfrah who, with his work, created not only the material environment, but also a less tangible yet abounding ideological space that conditioned my own work. Venice also introduced me to the term ‘cultural mediator’ which subdues ‘invigilator’ and comes closer to what an ‘ambassador’ does. Indeed, mediating between the exhibition and the public, I helped facilitate visitors’ understanding of it.2 I had to re-present Akomfrah’s work to visitors who would ask me: ‘can you explain?’ Below is an overview of the exhibition, another endeavour at re-presenting it for the purpose of writing.

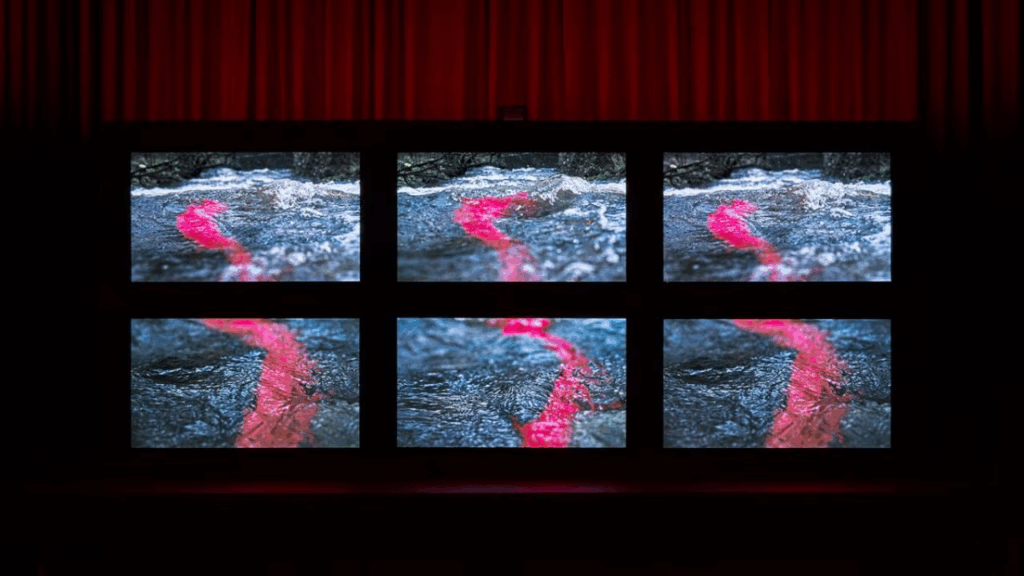

In keeping with Akomfrah’s interests over his four-decade-long career, the exhibition presented postcolonial histories of the Global South and diaspora communities in the UK through an audio-visual engagement. With a focus on concepts of time, memory, water and deep listening, among others, the pavilion included a sprawling collage of archival images and newly shot videos projected over 47 screens. These covered a disparate array of political events from the history of the twentieth century across five continents – from Kenya’s Mau Mau Uprising to the Korean War and Vietnam War, from Bangladesh’s floods in the 1980s to the life of the Windrush generations in the UK – as well as environmental concerns – such as the use of insecticide during WWII – and cultural phenomena – as in the evolution of Caribbean musical cultures. Borrowing its structure from poet Ezra Pound, the pavilion was organised in eight ‘cantos’. The central motif of ‘bodies of water’, according to the exhibition guide, is a reference to Gaston Bachelard, the concept of ‘acoustemology’ a nod to Steven Feld, and the colours in the exhibition design are inspired by Mark Rothko. Quotes from Pauline Oliveros, Édouard Glissant, Rachel Carson and bell hooks were stencilled in gilded script above the stately doorways of the neoclassical building, each leading into a canto. The visuals within the exhibition design were consistent with Akomfrah’s cinematic style, usually described as contemplative and essayistic. Similarly immersive was the sound which bleeds across all rooms. Dedicated to ‘listening as a form of activism’, one canto featured a sound installation Akomfrah produced in collaboration with Dubmorphology.

This exhibitionary set up formed the material conditions of my daily work as invigilator. After being on site for a while, more embodied responses to the work arose as my tasks involved not only watching over visitors, but also watching (and hearing) Akomfrah’s installations. My extant scepticism toward the utilisation of identity and representation in the fellowship I was part of and the long working hours I spent in the pavilion oriented me to scrutinise and consider several layers of representation activated in and around Akomfrah’s work. First, there is the mimetic and discursive representation of the various subject matters in Akomfrah’s work as briefly summarised above. Second, the political representation occupied by Akomfrah (and I) at the national and institutional level that is fundamentally framed by the discursive level of representation. Third, the formal function of representation in the cinematic apparatus that Akomfrah employs to actualise the previous two levels of representation. Witnessing how these representations have been communicated to visitors and having had myself to liaise with them, I have since reflected on the methodology of this exhibition and Akomfrah’s artistic practice more broadly.

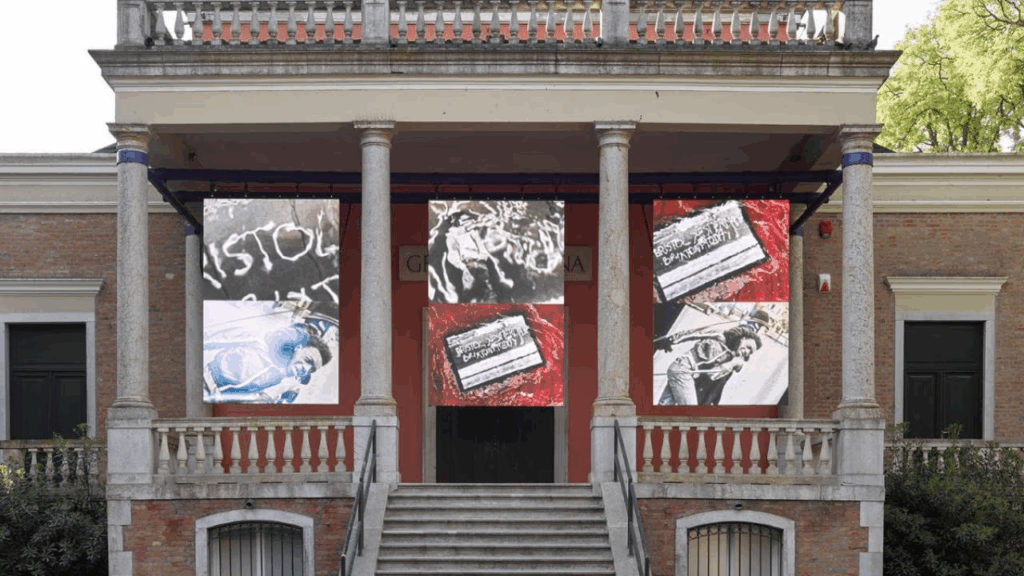

Let me unpack the experience of the exhibition further, starting from the beginning. Entering the Giardini della Biennale, and walking up the gravelled steady slope of Viale Trento, the British Pavilion can be found sitting at the top, allegedly the highest point of Venice.3 The facade exhibited three large LED screens showing fragmentary imagery of water, plants, and people, accompanied by indefinite sounds of water, drumming and humming. The entrance proved confusing to the visitors. Located at the back of the building, through the basement door, this design by Akomfrah and curator Tarini Malik was meant to invoke the hierarchy of English country houses where only servants entered through the backdoor.4 As this intention was ever only conveyed through a podcast interview, the visitors often arrived at the main entrance, simply unsure of the wayfinding. They often asked me what country the pavilion represented, since the nameplate at the front was blocked off by the LED screens, which are, again, envisioned as an artistic intervention on the neoclassical building.5 Regardless, most visitors were pleasantly surprised after entering the building by the peculiar colour scheme of purple and yellow in the panels with the exhibition title and the posh-looking setup of dim lights and velvety walls in the basement. As most visitors were not familiar with Akomfrah’s oeuvre, they did not know that the colour was a self-reference to his 2017 work ‘Purple’; nor could they perceive the significance of the basement space which had only been used for exhibition once before in the pavilion’s eighty-year history.6 These references, along with the designed path, were emphasised by the British Council to all of us fellows but omitted, presumably more unwittingly than deliberately, in the communications with the average visitor. Eliding most visitors, they were almost an insider layer for experiencing the exhibition based on exceptional, or even exclusionary, institutional knowledge.

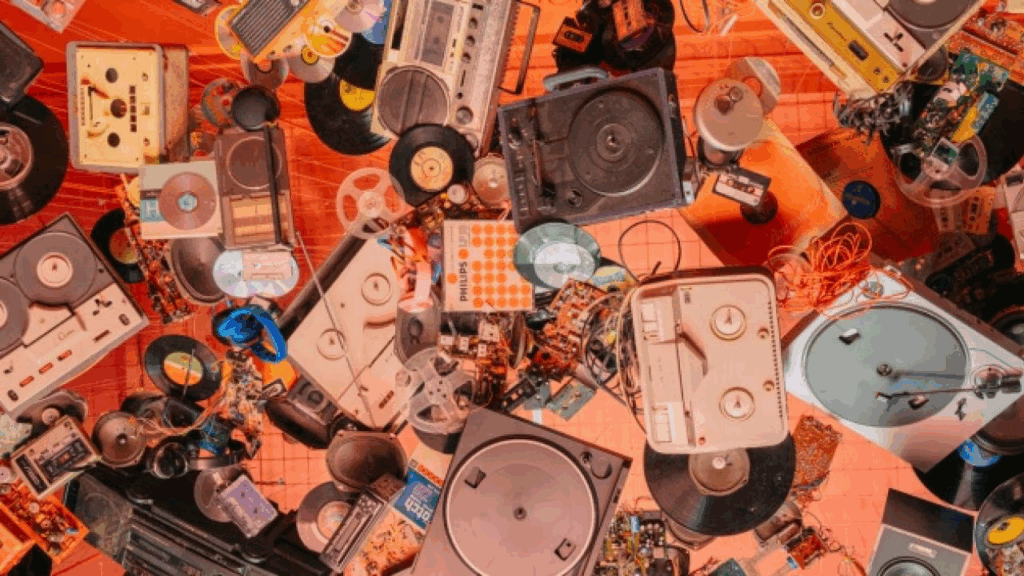

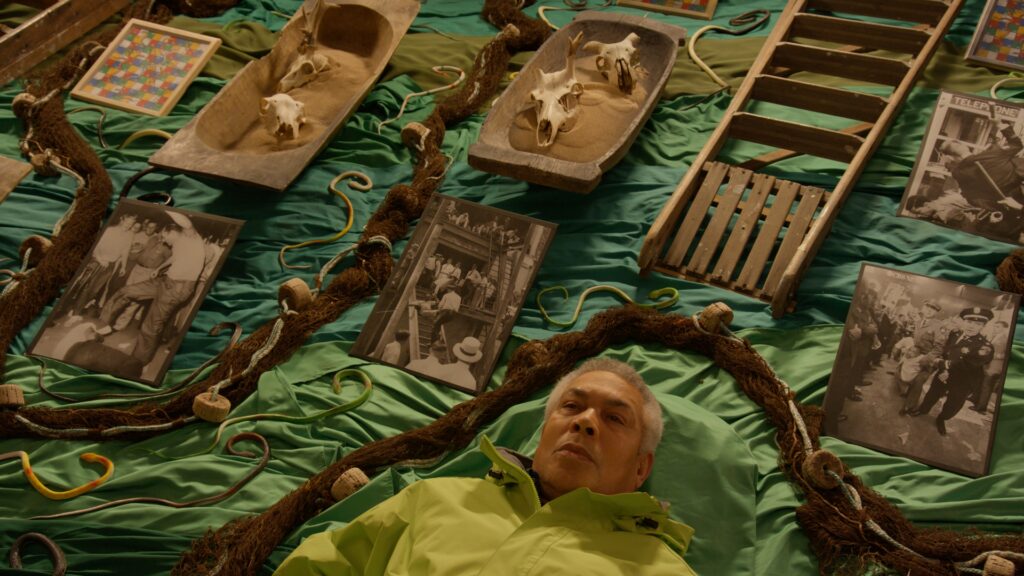

Where the references are spelled out, for example in the wall text, I felt a lag between the messages and how they are conveyed. Although the exhibition expressed a focus on the sonic, there is no guidance for active listening with overflown visuals competing with the sound. The sound installation made of over 400 outmoded audiophonic devices hanging from the ceiling – the only canto without screens – was louder in sight than sound. Depth was renounced for the sake of breadth in the ways Akomfrah engaged with both his theoretical references and his visual subjects. Nuances and differences across the planetary become smoothed out in the tableaux vivants, set and shot in identical ways, only with different people (of different ethnicities, genders, ages, etc.) and their corresponding objects of cultural association. The hyper-optical treatment lent a sense of flatness to the mise en scene, making objects and subjects feel unreal as if in an advert for high-resolution TV screens. The historical specificities encoded in the archival materials were not explained to the visitors who are otherwise inundated in their over-abundance. The exhibition read/sounded like a poem of multiple stanzas structured by the same meter and rhythm, just with different bricolages of words that are forced to rhyme.

In two of the cantos, the wall texts were mixed up. Sitting in the corner overseeing the two rooms, I was amazed that no visitors seemed to notice the inconsistency between the textual and the visual. At this point, drowned in the cacophony of information, does it really matter whose history this was or what bodies of water those were? I found fault especially with the way Akomfrah represented his subjects in the tableaux vivants, described in the exhibition guide as characters ‘who represent the diaspora in Britain’ through whom ‘the artist tells stories from the five continents’.7 On several screens we see them staring out into the indefinite beyond or lying on a set amidst a meticulously arranged array of objects, expressionless and voiceless. A certain stillness from the slow panning of the high-resolution camera renders them almost lifeless. Each person is destined to perform a specific identity and activate the corresponding histories that Akomfrah set out to represent. Instead of ‘speaking nearby’ – a practice encouraged by fellow filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha – Akomfrah speaks about his subjects, turning them into stand-ins of predetermined meanings and thus collapsing the space for new knowledge and new relations. As an instrument of philosophy, a means to an end, the subaltern in Akomfrah’s tableaux vivants cannot speak.8

Maybe representing these ‘characters’ was never Akomfrah’s intention; maybe their hollowness was a deliberate feature of a ‘radical aesthetic’. But this tokenised representation of the postcolonial subjects is, ironically, a direct result of Akomfrah’s own selection to be the representative of the UK at the 2024 Venice Biennale, a function he duly performed. Akomfrah has described his commission as an ‘ultimate accolade’.9 A lot of effort and resources went into his exhibition,10 although the fact that fellow artist Sonia Boyce had won the Golden Lion for her representation of the UK in 2022, made it unlikely for the British Pavilion to gain the award for two consecutive editions.

As a Chinese national, I also had mixed feelings about the exhibition’s title drawn from the classical Chinese poet Su Shi 苏轼, art name Dongpo (东坡), who led a life of political exiles in the eleventh century. Despite Su being a household name in China and a mandatory part of the school curriculum whose poems I learnt as a kid, I found it difficult to locate the origin of this line, said to be from ‘Poem 83’. After some research, I came across a bi-lingual poetry book of Su with the exact same title, revealing the Chinese original. ‘Listening All Night to the Rain’ was extracted from the penultimate line of ‘林下对床听夜雨’ in the poem ‘雨夜宿净行院’11 which in fact describes Su Shi not only listening to the rain, but also staying under the groves (‘林下’) with two beds (‘对床’), one left empty for his younger brother Su Zhe 苏辙 whose presence is dearly missed.12 The poem then ends on a note of desolation, in the silent dark night.13 While the exhibition text attests to a debt of inspiration to Su Shi’s poetry that ‘meditates upon the transitory nature of life during a period of political exile’ and a commitment to ‘listening as a form of activism’,14 this specific line is certainly not the most representative for any reader of Su Shi. Regardless, the presence of Su Shi’s name in the last canto attracted many Chinese visitors to take photos, although they were probably more surprised than moved by this unexpected reference at the very end of the exhibition. The reproduction of ‘Poem 83’, however, was most disappointing: combining the penultimate line with the previous one, Akomfrah belied the ‘cantos’ of traditional Chinese poetry where the penultimate line should be grouped with the ultimate. There is an affinity here in Akomfrah’s approach to Chinese poetry with Ezra Pound, the other poet referenced in the exhibition, who famously translated classical Chinese poems into English without knowing the Chinese language. While a discussion of appropriation and exoticisation would require more space, it suffices here to say that Akomfrah did not treat some of his references with the same care afforded to others.15

Maybe what Akomfrah really wanted to do was to talk about philosophy. Initially, I was excited by the wealth of philosophical references in Akomfrah’s work, which I was not only intellectually familiar with but also emotionally invested in. While Akomfrah’s work is often described as dense,16 the exhibition became, on the contrary, too transparent for me. The predominance of a specific tradition of Western philosophy, which has historically elevated the thinking mind over the feeling body, debilitated the possibility of tapping into alternative emotional and embodied epistemologies that could have allowed new meanings, knowledge, and poetics to emerge from his work. I became weary of the finite set of vocabularies I had to repeat every time I explained the exhibition to confused visitors. I struggled with the inadequacy of generic terms and a desire towards more specificity, including why certain concepts were chosen over others and how Akomfrah arrived at such a collage. It was curious to me, for instance, why Akomfrah did not explicitly reference Paul Gilroy’s work on the Black Atlantic in a (British) exhibition themed around water, postcolonialism, diaspora, and ‘listening as a form of activism’ – themes which are all prominent in the latter’s writings. Instead, he opted for French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s writings on ‘bodies of water’ in The Poetics of Reverie: Childhood, Language and the Cosmos (1960) – a book that is decidedly more concerned with poetic consciousness than postcolonialism and activism. Despite the abundant visual and textual references to Black communities and Black thinkers and activists in the pavilion, the search for the word ‘black’ in the exhibition guide returned only three mentions. Is Akomfrah intentionally avoiding racial and ethnic representation for fear of the normative or want of the radical?

Thirty years ago, art historian Kobena Mercer famously described the burden of representation weighting on ‘Black Art’, an expectation that cast Black artists in the role of spokespersons for a culture in its entirety. While this burden of representation certainly continues to exist today for artists from minoritised backgrounds, Akomfrah’s position in the visual arts has changed tremendously since he started making work in the 1980s. He now stands at the top of ‘the hierarchy of access to the institutional spaces of cultural production’17 that, according to Mercer, effects the burden of representation for Black artists. While that burden has certainly shifted for Akomfrah over the years, we should ask: who and what does Akomfrah’s work represent in this new context?

In the 1980s, non-representational tactics enabled Akomfrah and his fellow artists in the Black Audio Film Collective to work against the grain of reductive demands of racial-ethnic representation in art and to resist the burden Mercer described. However, taken out of its historical and socio-political context, the use of non-representation and abstraction are not, in themselves, a magic formula for radicality. Akomfrah’s turn to philosophy might justify his aesthetic strategies of abstraction, but intellectualism alone cannot guarantee the radical aesthetic he wished to sustain. When philosophy becomes a fixation, intellectual complexity then risks fossilising into an elitist formalism detached from the very grassroot struggles Akomfrah’s work intends to engage with. Etymologically, the word ‘radical’ originated from ‘root’, and it would have been helpful for Akomfrah to sincerely think through the roots of his own artistic practice to resurface genuine radical works. Philosophies have roots of their own as well, and the disproportionate amount of US-American and continental European philosophical references in an exhibition about the ‘Global South’ is also worth reconsidering. Knowledge production is even more deeply embedded in ideology and power relations than artistic production, and renewed sensitivity to the cultural and socio-political landscapes is needed in both kinds of work.

Akomfrah started his film practice in the 1980s with single-channel experimental films and documentaries as a member of the Black Audio Film Collective (1982–98). The multi-screen installations he has become known for in recent years did not come into his practice until the 2010s, under his own studio and production company Smoking Dogs Film (1998–). While still working in the realm of the essay film, this decisive turn in Akomfrah’s practice happened somewhere around the making of the documentary The Stuart Hall Project and the parallel multi-screen installation The Unfinished Conversation in 2013. Two years later, a new multi-screen installation, Vertigo Sea, was shown at the 56th Venice Biennale. In fact, Akomfrah’s spatial film practice can be seen as a continuation of expanded cinema, a movement and concept that emerged in the 1960s, and one of whose most distinctive features was precisely the turn from singular to multiple screens.18 The multiplicity of screens or projections, alongside other interactive elements such as live performances, challenged the boundaries of traditional cinema and signified a multiplicity of temporalities, spatialities, narratives, and modes of spectatorship against the one-way relationships instituted by classic cinema. While this fragmentation of viewing experience has become ubiquitous in our digital age, Akomfrah’s multi-screen practice continues to explore the possibility of realising multiple ontologies through ‘the dialectical possibilities of montage.’19 Attempting to create what he calls ‘digitopia’, Akomfrah explores the potential of the digital ‘as promise, as reinvention, as a dissident echo in a tale of postcolonial becoming’20 for Black (and) diasporic subjectivities.

In 2014, artist Renée Green organised a symposium at MIT titled ‘Cinematic Migrations’, the culmination of a two-year collaborative research and production project in which John Akomfrah and fellow BAFC member Lina Gopaul participated as artists in residency. Among others, guest speakers at the symposium included artist Arthur Jafa, who had just completed his video work Apex, and Fred Moten, fresh off the publication of his co-authored book The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (both 2013). In his presentation, Moten described the work of Green, Jaffa, and Akomfrah as an ‘anacinematic practice’ that breaks away from the history of twentieth-century cinema, animated by the exclusion of Black subjects as the negative of humanity. During the discussion that followed, Akomfrah asked about the possibility of a post-cinematic space, expressing his dilemma between giving up the cinematic with its racist subject formation and holding on to the making of a ‘Black cinema’ that still inevitably carries traces of that cinematic language. What Akomfrah did not realise was that he was already working in a post-cinematic space and that the cinematic and post-cinematic, the subject and post-subject, are more dialectical than binary. As Moten put it: ‘The transcendence of the work … exists precisely as a function of the imminence of what’s in the work.’21 That is, the impossibility of Black subjects and the oxymoron of Black cinema stimulate filmmakers to break existing grounds and find new openings through their dangerous proximity to the norms of cinema: there is no a priori radicality.

In a 1988 interview with Black Audio Film Collective conducted by Paul Gilroy and Jim Pines and focusing mainly on Handsworth Songs (1986), questions of Audiences / Aesthetics / Independence are shown to be intertwined.22 Nearly four decades later, I believe they still are. With the present global reception and recognition of Akomfrah’s work, epitomised by the ‘accolade’ of representing the UK at the Venice Biennale, it is perhaps time for Akomfrah to reappraise his aesthetic quest and the role it plays particularly in relation to audiences both old and new. Leaving the British Pavilion at the end of my fellowship, what stayed with me was a short melody hummed by a female voice that all us fellows memorised while unable to pin down its source. Less burdened by the weight of institutions, it is these elusive and embodied connections that I hope to hear more in Akomfrah’s work.23

- 1. My criticality toward representation fuelled my creative project within the fellowship: a performance during working hours called ‘straniero’ (‘foreigner’ in Italian, referencing the Biennale’s title ‘Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere’). Mimicking the role of the ‘ambassador’ by wearing a Chinese-usher-style sash with the word ‘straniero’ printed on it, the performance was conceived in response to both the institutions of the British Pavilion and the Venice Biennale, and meant to highlight the often-overlooked labour of invigilation. See 施雨 freya shi (@shiyufry), ‘straniero’, Instagram post, 13 July 2024, available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/C9WxuwOMl9S/ (last accessed on 15 May 2025).

- 2. As part of my project, I also led a tri-lingual (Chinese/English/Italian) reading workshop that explicates and expands on references in Akomfrah’s exhibition. See Youssef Hesham, ‘Freya Reading Workshop by Youssef Hesham’, available at: https://lightroom.adobe.com/shares/78aef85910fd402aa989abd47d714ff6 (last accessed on 15 May 2025).

- 3. ‘John Akomfrah and Tarini Malik, Presented by Burberry’, Talk Art podcast, 19 April 2024, available at: https://shows.acast.com/talkart/episodes/john-akomfrah-and-tarini-malik-presented-by-burberry (last accessed on 15 May 2025).

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Interestingly, the facades of the French and the German pavilions, standing on opposite sides of the British Pavilion, went through parallel fates, though in a more subdued manner.

- 6. The staircase and the lift connecting the basement to the first floor were also newly built for this exhibition.

- 7. T. Malik, ‘Curator’s Introduction’, in Listening All Night to the Rain. Exhibition Guide, available at: https://venicebiennale.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/bc_art24_digital_guide_a6.pdf (last accessed on 15 May 2025).

- 8. Gayratri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak’, in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, ed. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, pp.66–111.

- 9. This accolade is very much in line with Akomfrah’s appointment as CBE in 2017 and knighthood in 2023. See Sir John Akomfrah on Receiving ‘the Ultimate Accolade in an Artist’s Life’ | 60th Venice Biennale, 2024, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wuvf2IqEbQ (last accessed on 15 May 2025).

- 10. Besides funding from private donors such as Burberry, British Council has also partnered with Frieze for the 2024 pavilion, marking the first time that an art fair ever sponsored a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

- 11. This translates to ‘stay at Jing Xing Yuan on a rainy night.’

- 12. This is based on historical scholarship and common knowledge in China about the personal context of Su Shi’s writings. The idiom ‘夜雨对床’ or ‘two beds on a rainy night’, meaning friends or brothers having an heart-to-heart talk after a long separation, is originated from Su Shi and Su Zhe’s fraternal relationship. See 张春生, ‘二苏“对床夜话”’, available at: https://files.mssswhyjy.com/sansu/xslw/detail?uid=1000000000000078397.

- 13. The Chinese original is ‘静无灯火照凄凉’.

- 14. T. Malik, ‘Curator’s Introduction’, op. cit.

- 15. This lack of care was evident also in the installation of Canto VII (in reality Canto VIII) where footage of the Vietnam War was shown.

- 16. Even if one could argue that the work embodied something of Glissant’s right to opacity, isn’t its overreliance on textual references to communicate with the visitors a fault of the work, rather than the visitors?

- 17. Kobena Mercer, ‘Black Art and the Burden of Representation’, Third Text, vol.4, no.10, 1990, p.65.

- 18. The term ‘expanded cinema’ was coined by Stan Van Der Beek around the mid-1960s while the first book on the subject was published by Gene Youngblood in 1970.

- 19. Alessandra Raengo, ‘The Jurisgenerativity of a Liquid Praxis: A Conversation with John Akomfrah’, Liquid Blackness, vol.5, no.1, 1 April 2021, p.132.

- 20. John Akomfrah, ‘Digitopia and the Spectres of Diaspora’, Journal of Media Practice, vol.11, no.1, 2010, p.18.

- 21. Fred Moten, ‘Cinematic Migrations’, 7 March 2014, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AIjipUxCYYs.

- 22. Paul Gilroy et al., ‘Audiences/Aesthetics/Independence: Interview with the Black Audio Collective’, Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no.35, 1988, pp.9–18.

- 23. ‘Listening All Night to the Rain’ has travelled to Amgueddfa Cymru/National Museum Wales (Cardiff), on view from 24 May to 7 September 2025. According to the exhibition guide, future tours include Dundee Contemporary Arts (Dundee) and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary – TBA21 (Madrid) in 2025 and 2026.